The Motel

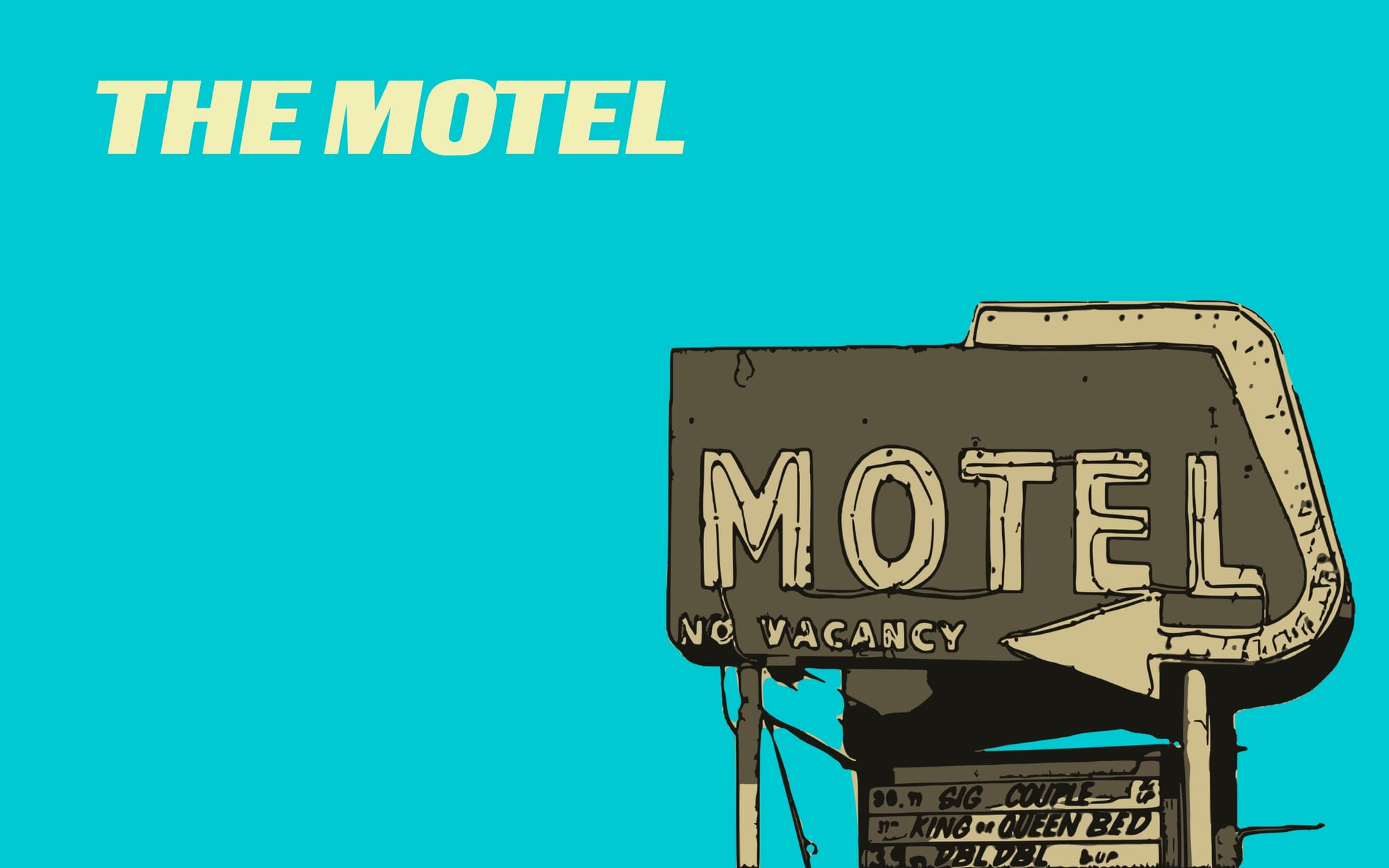

They would let me turn on the big neon sign at sundown and switch it from “Vacancy” to “No Vacancy” as it was warranted. The rest of the sign was always lit up.

It was 1980, and the last two years had been as frightening for my family personally as they had been for the rest of the country. The mines where my stepfather worked had closed down in 1978. This had started off a two-year saga of wandering for him and my mother. An uncle on my father’s side owned an RV dealership, and my mom and stepdad had gotten a hold of a camper van called a Honey Bee. It was a big white thing of aluminum siding decorated with a gold stripe and a little cartoon bee mascot pasted on the side. There was a compartment over the cab with bunks and a window that gave me an aerial view over the highway. Whenever I rode in the Honey Bee, that crow’s nest was my seat. This allowed me to announce the obvious with the authority of a mentally underdeveloped god. “Stop sign!”

But I actually didn’t ride in the Honey Bee that often. Our recreational vehicle was not so much for recreation. Its larger purpose was so that my parents could drive around the country desperately following rumors of possible employment. Sure, Arizona sounded exotic and fun to me at the age of six, but when your goal is to go see a tire warehouse doing an open call for new hires, and not the Grand Canyon, I’m sure some of the shine rubs off.

I didn’t go on that trip anyway. While most of my stepsiblings were old enough to get places of their own or stay at friends’ places, my sister Amy and I were left in the care of my maternal grandparents. We stayed at the cheap motel they owned on the outskirts of town, and they would let me turn on the big neon sign at sundown and switch it from “Vacancy” to “No Vacancy” as it was warranted. The rest of the sign was always lit up. It was one of those Route 66 bits of signage that announced that not only was the future right around the corner, it also swooped and swirled at angles beyond your understanding of the rudimentary physics that you were used to, Mr. Flintstone. The fallacy of this announcement was given away, however, by the name of the place, the Mine La Motte Motel. It was named after the very thing that had just died and taken the town with it. The mine was quickly receding into the past, as were all of our Oscar Niemeyer dreams. No hover cars for us. Just the Honey Bee.

Though it must be said that the Honey Bee was pretty cool.

Staying with my grandparents was its own strange adventure. My grandfather—known to me at that time only as Bull—would get me up early in the morning, and we would get out his hunting dogs to see if we could chase out a few rabbits. Many of the motel’s guests were woken up by gunfire as Bull took potshots at anything that moved in the underbrush out behind the building, no more than twenty feet from the guest rooms’ bathroom windows. They’d come rushing out of their rooms just in time to see him carry a dead carcass up to the skinning post, a tall piece of wood with a nail stuck in it. He’d hang whatever he’d shot from the nail, wave to the paying customers with the hand holding the shotgun, and get out his pocket knife. This was usually enough to ensure that everyone was checked out of the motel on time.

If nothing worth shooting came up that day—and it should be said that almost nothing ever did—we would go down to the Pig for lunch. The Pig was a barbecue drive-up joint down the road, with a big friendly pig in a waistcoat painted on the outside, waving to people as they passed. Your sandwich came to you wrapped in white butcher paper, and your fries came in tablecloth-patterned cardboard boats. All of it was soaked in grease and sticky-sweet barbecue sauce. I was in heaven.

Finally, another uncle on my father’s side said he could get my stepfather work at a GM plant if we moved to a St. Louis exurb called St. Peters, a suburb of a suburb called St. Charles. So, the rolling unemployment sideshow came to a stop, the Honey Bee was sold, and we were transplanted. For my family, things were looking up. For me personally, however, this was a disaster. When I was moved to St. Louis, I was the most miserable six-year-old in the world. All I wanted was to go back to Fredericktown. I had been a popular kid in the first grade; there was a little dark-haired girl in my class who had taken a liking to me, and all of my friends were within walking distance of my house. I had had a good thing going down there. In St. Peters, I had no friends, we were poorer than all the other kids, and my southern accent, which was thick and trashy when I was young, made me an outcast. I hated it there. There were no woods, the kids were mean, and I was miserable. I sulked for what seemed like years.

I was unable to see this from my parents’ perspective. Until 1977, Fredericktown, Missouri, had been the cobalt capital of the world. Then it was discovered that, actually, Zaire was the cobalt capital of the world. The two years between the closing of the mine and our landing in the Sutter’s Mill subdivision must have been the height of uncertainty. With a family whose numbers fluctuated between four and twelve, depending on who was crashing unannounced, and many of those members being of school age, with all of the needs that that implies, the sudden loss of half their income must have struck my parents like a flaming meteor of shit careening out of the sky.

But now, things were different. My mother suddenly had a new house, bigger and more modern than the one we had lived in before the Honey Bee. She was also a nurse and had found work easily. What’s more, the house was in a nice place. It was a neighborhood where there was a public pool and rules about keeping dogs on leashes. In Fredericktown, my mom would wake up most mornings to find that her brother Donny’s hunting dogs had wandered down the road from his house and were sleeping on one side of her porch and pissing and shitting on the other. She had finally put a stop to that one July 5th when she had snuck out the back door and around the house before breakfast with whatever was left from the previous day’s stock of fireworks and proceeded to fire at the hounds with screaming bottle rockets. That wouldn’t happen in Sutter’s Mill. In Sutter’s Mill, there were rules about such things. No more dogs and no more Donny showing up drunk at noon wanting to know what in the hell she had done to those dogs to make them hide under his house and refuse to come out.

So, yes, it was a step up in the world. We were moving on up, indeed. But I couldn’t see it. I missed the motel. I missed the sound of car tires crunching on the white gravel as they pulled into the circular drive. I missed the Formica top of the reception desk that sat in the wood-paneled office and the sign-in book, with its Bible-thin pages and its pen on a chain. I missed the way people just showed up anytime, day or night, coming or going anywhere. I missed the idea that we sat right on an artery that could take you anywhere if you just went out there and eased yourself into the stream of traffic, slowly at first and then whisked away into the unknown. I would sit outside on the little hill next to the motel office/my grandparents’ house—a hill that I didn’t realize was covering a septic tank—and stare at the cars going by on the road. I would wait for one to pull in, eager to see the license plates that would fire my imagination with the enticing unknowns of faraway lands like Indiana or New Mexico. There was a whole new Mexico; how could you not want to go and check that out?

So, yes, we had moved to St. Peters and my parents had moved into the house where they would live for the next 45 years. But part of me stayed at the motel. At least for a little while, until it finally got its shit together and dragged the rest of me out onto that road. It must have happened right around the time that they tore the old place down and carted off that magical sign. No vacancy.